Indian Concepts of the Afterlife: Karma, Reincarnation, Moksha, and the Cyclical Nature of Life and Death

Explore the profound Indian philosophies of the afterlife—where karma shapes destiny, reincarnation fuels the soul’s journey, and moksha offers ultimate liberation from the eternal cycle of life and death.

CULTUROSCOPE

In Indian philosophy, the afterlife is a deeply interconnected concept that blends karma, reincarnation, and moksha, forming a cyclical view of life, death, and rebirth. This intricate framework helps answer profound existential questions—what happens after death, and how does one achieve liberation? The Indian worldview emphasizes the continuity of the soul rather than its finality. Through this lens, life is not a singular experience, but part of an ongoing journey, where actions (karma) across lifetimes influence the soul’s fate. These ideas, rooted in ancient texts like the Bhagavad Gita and Garuda Purana, provide profound insights into the human spirit’s quest for meaning, transcendence, and liberation.

Origins, Symbolism, and Evolution Over Time

The concept of the afterlife in India originates from the Vedic texts and evolves through various philosophical schools over time. The Rigveda and Upanishads introduce early ideas of the eternal soul (atman), which does not perish with the body but instead transcends physical death. However, it is the Puranas, particularly the Garuda Purana, that offers detailed descriptions of the soul's journey after death, elaborating on the consequences of one’s actions in life. This journey is not linear, but cyclical—reflecting the essence of reincarnation and karma in Hinduism.

In early depictions, Yama, the god of death, is portrayed as a stern but just figure who judges the soul’s actions and determines its fate. Over time, the portrayal of Yama’s court and the process of judgment evolved, taking on more elaborate and intricate forms in later texts, such as the Garuda Purana. This evolution mirrors the increasing complexity of the Hindu understanding of the afterlife, where the soul's journey after death is not only about punishment or reward but also about spiritual progression.

Human Nature: Fear of the Unknown and the Desire for Meaning

Central to the Indian afterlife belief is humanity’s intrinsic fear of the unknown and the desire for meaning beyond this physical world. Death is viewed as a transition, not an end, offering a way for humans to understand the impermanence of life and to find a path toward spiritual fulfilment. In a world marked by suffering and impermanence, the promise of reincarnation and liberation through moksha offers solace. Karma, or the law of cause and effect, ensures that one’s actions—good or bad—have consequences that shape their fate in subsequent lifetimes. This universal law addresses human concerns about justice, right and wrong, and the moral fabric of existence. Thus, the afterlife is deeply tied to personal responsibility, as individuals are empowered to shape their spiritual destinies through their actions.

Reincarnation vs. Eternal Destinations

The Indian belief in reincarnation stands in contrast to many Western concepts of eternal destinations such as heaven or hell. Reincarnation allows for continuity: life is seen as a series of cycles, with the soul transitioning from one body to another until it reaches liberation. The soul is never truly lost, but its state of existence varies depending on the deeds performed in past lives. In contrast, eternal destinations—such as heaven (Swarga) or hell (Naraka)—in Indian mythology often represent a temporary stop rather than a permanent state.

According to the Bhagavad Gita, the soul is immortal, and death is merely the shedding of the body: "Just as the boy puts on new clothes and gives up the old ones, similarly, the soul accepts new material bodies, giving up the old ones." This cyclical view emphasizes the soul’s journey—not its finality. The destination of the soul is not permanent; it is a point on a larger spiritual journey. Only through the realization of the self’s oneness with the ultimate reality (Brahman) can the soul attain moksha, escaping the cycle of birth and death. This contrasts sharply with the finality present in the Abrahamic conceptions of an eternal afterlife, where the soul’s fate is sealed at the moment of death.

The Journey of the Soul to Yama’s Court and Depictions of Hell and Heaven

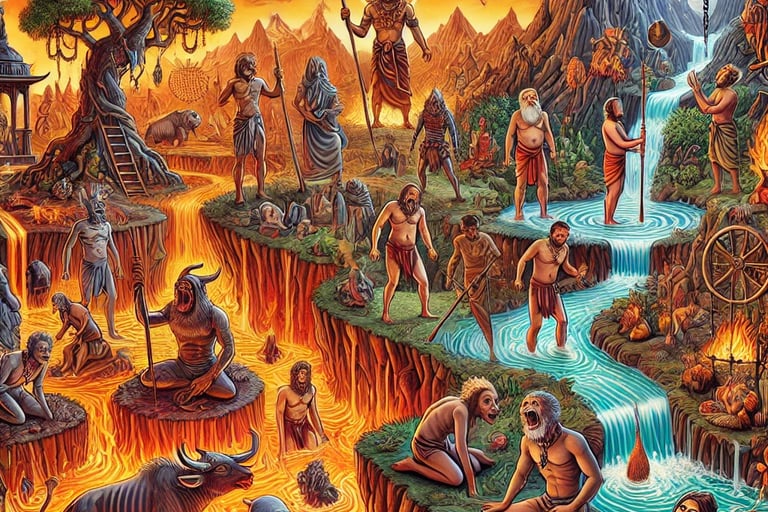

In Indian mythology, one of the most vivid depictions of the afterlife is the journey of the soul to Yama’s court, where it faces judgment. This journey begins immediately after death. The soul is said to leave the body and traverse a series of pathways, crossing rivers, mountains, and gates to reach the divine court of Yama. Along the way, the soul encounters various challenges based on its deeds in life. Those who have committed sins face torment in the various Narakas (hells), where they endure suffering until their karmic debts are paid.

In the Garuda Purana, there are detailed descriptions of Naraka, each hell tailored to the nature of the sin committed. For example, the souls of those who were violent in life are subjected to hells filled with burning, while those who indulge in greed might be tortured by unbearable thirst. The depiction of hell is not merely punitive but serves as a transformative experience, designed to cleanse the soul before it moves on to its next life or ultimately achieves moksha.

On the other hand, the virtuous are taken to Swarga, or heaven, where they are rewarded for their good actions. However, even this is not permanent. The soul, having accumulated merit, enjoys the fruits of its good deeds but eventually descends again to the mortal world once its store of good karma runs out. This cyclical concept emphasizes that neither punishment nor reward is eternal; both are part of a larger cosmic balance.

Final Judgment, Crossing Thresholds, and the Transformative Journey

The Indian myth of the afterlife is replete with motifs that resonate across cultures. One of the most profound is the final judgment—a judgment that occurs not at one moment but throughout the soul’s journey. Yama, as the god of death, is both a judge and a guide, leading souls through the consequences of their actions. In Hindu mythology, this judgment occurs at Yama’s court, where the deeds of the soul are weighed on a metaphorical scale, determining whether it will be reborn or granted liberation.

The crossing of thresholds is another universal motif, where the soul crosses physical or metaphysical barriers to enter the afterlife. The Vaitarani river, in particular, is a symbol of this threshold. It is said to be a difficult crossing for the soul, filled with dangers that can be overcome only by a pure heart. This river, like the Styx in Greek mythology, marks the boundary between the material world and the spiritual one, where the soul must shed its earthly attachments before it can ascend.

Lastly, the transformative journey of the soul is central to the Indian afterlife concept. The journey through Naraka, the crossing of the river, and the eventual attainment of moksha represent not just the consequences of one's actions but also the soul’s purification and evolution. The soul moves closer to its ultimate goal: reunion with Brahman, the source of all creation. This transformative process is both a metaphor and a reality, symbolizing the soul’s progression toward enlightenment.

Metaphors and Symbolic Imagery

Indian afterlife mythology is rich with symbolic imagery and metaphors that bring the journey of the soul to life. Rivers, such as the Vaitarani, represent the soul's transition, carrying it away from the material world toward the spiritual realm. Gates in texts like the Garuda Purana symbolize entry into new realms of existence, where the soul undergoes either purification or judgment. The imagery of fire and light in the description of Naraka and Swarga suggests both destruction and transcendence, emphasizing the dual nature of the afterlife as both a place of suffering and eventual liberation.

The Indian view of the afterlife, encapsulated in the concepts of karma, reincarnation, and moksha, presents a vision of life and death that is both profound and transformative. In this framework, death is not an end but a continuation, with each lifetime offering an opportunity for the soul to evolve and ultimately attain liberation. Through vivid depictions of Yama’s court, the journey across rivers, and the cleansing fires of Naraka, Indian mythology invites us to reflect on our own actions and their consequences, offering a rich spiritual roadmap to understanding the eternal journey of the soul.

Swarga vs. Moksha: A Brief Distinction

In Indian philosophy, Swarga and Moksha represent two distinct concepts of the soul’s journey. Swarga, or heaven, is a temporary realm of reward where the virtuous enjoy divine pleasures as a result of their good karma (punya). Governed by Indra, Swarga offers respite from earthly struggles, but it is impermanent—souls return to the mortal world once their merits are exhausted.

In contrast, Moksha is the ultimate liberation from the cycle of samsara (birth, death, and rebirth). It is eternal freedom, where the soul transcends dualities and unites with Brahman, the ultimate reality. Unlike Swarga, Moksha is not attained through rituals but through self-realization, detachment, and spiritual wisdom.

While Swarga motivates virtuous living by rewarding moral actions, Moksha inspires the pursuit of higher truths, marking the soul’s final liberation from all worldly and celestial bonds.

Subhalakshmi Buragohain

Hyderabad

Hell: A realm of judgment where actions meet their ultimate consequences.

Yama's Court: Where karma meets justice.